The Dike Worker

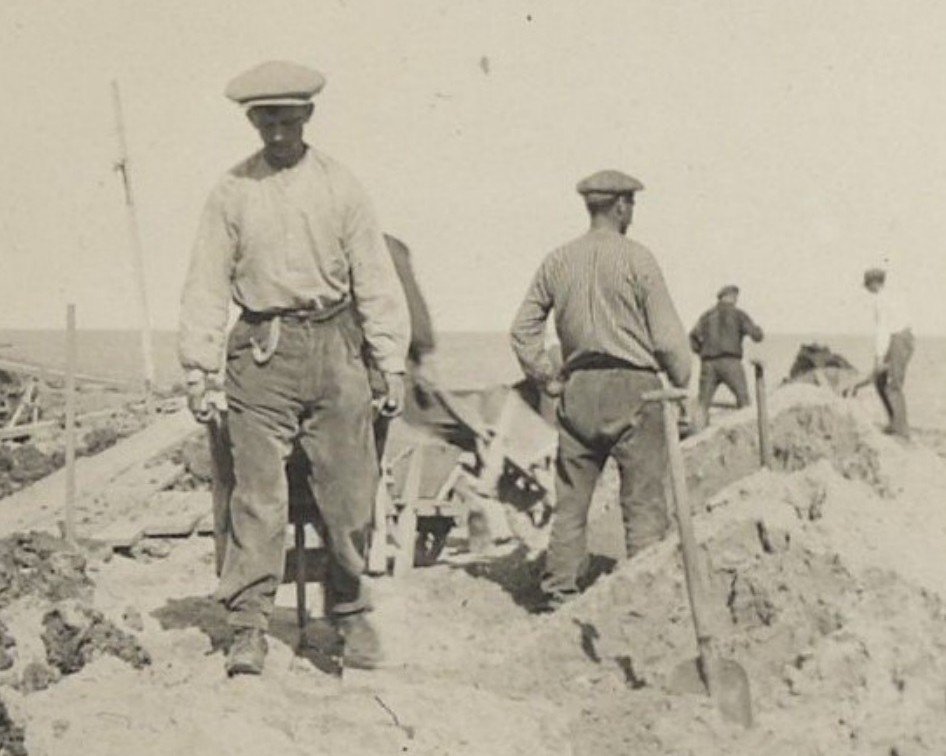

It is not known exactly when the Omringdijk was completed, but it was no later than the thirteenth century. Many generations of dike workers built and maintained the dike with shovels and wheelbarrows. The statue De Dijkwerker (The Dike Worker), created by Jan van Velzen, commemorates their important efforts. 'With thanks to all the workers of the past for their struggle against the water,' reads the plaque. And so it is. If they had not done so, we would not be standing here today.

The Omringdijk was created from separate small dikes. There was no 'Omringdijk project' initiated by higher authorities. There was no central authority in West Friesland to oversee such a project. Farming communities everywhere built low dikes to protect their land.

Everything involved in building or repairing the dike was done by hand: from digging to dumping and even transporting materials with wheelbarrows or carrying them by hand. Peat, manure, clay, and household waste—everything came in handy. The farmers themselves were responsible for building, maintaining, and repairing the dike. Each farmer was assigned a section of the dike by the water board to maintain.

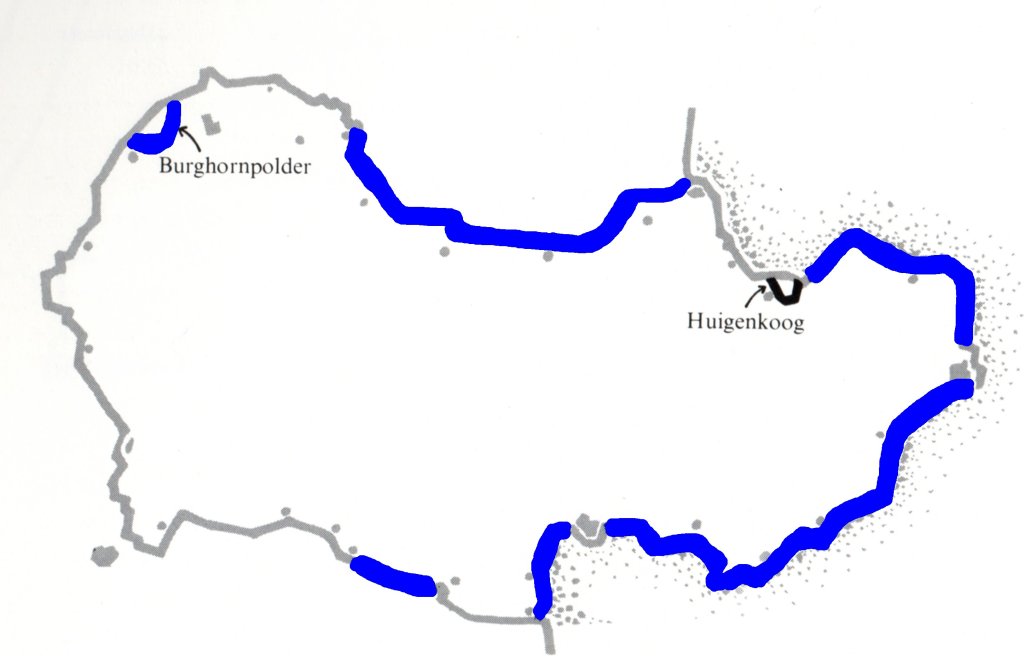

The dike maintained by the farmers was lower than it is today. It was not located directly on the sea. There was land in front of it that served to break the waves. In those days, society lacked the resources and organization to build a high, strong dike. Over the centuries, the land sank below sea level. The sea gained ground and swallowed up more and more of the foreland. Eventually, there was no other option but to create new foreland. To this end, a new dike, known as an infill dike, was built inland. A large part of the current route of the Omringdijk consists of infill dikes (blue on the map).

Maintenance by the farmers had its disadvantages. They lacked the time and expertise to build a high, stable dike. Moreover, not everyone took the maintenance of their section of the dike equally seriously. Such negligence on the part of a few farmers could have serious consequences.

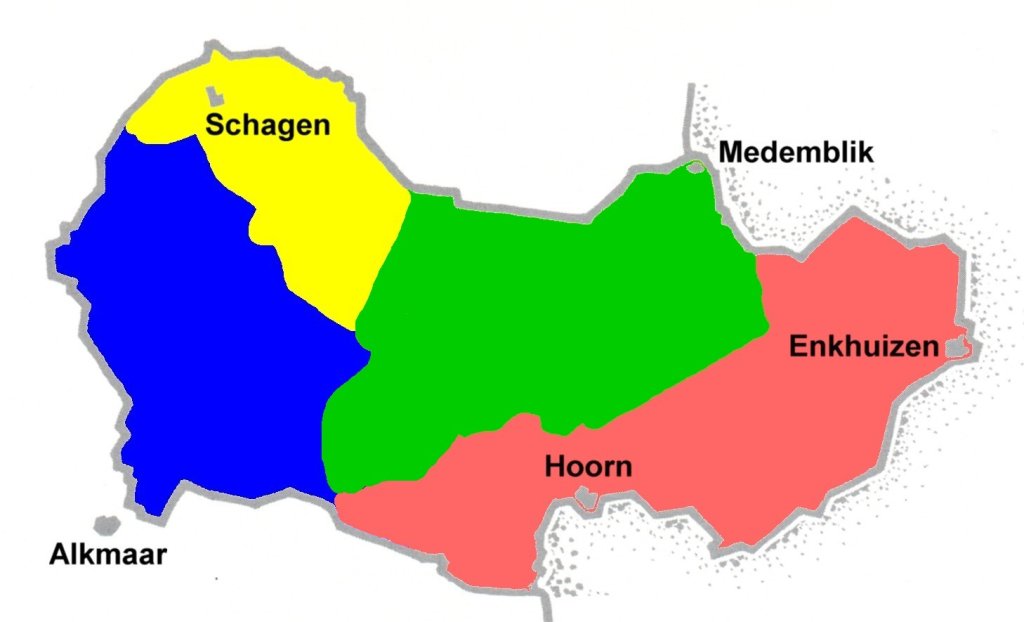

The dike was managed by four water boards: the Vier Noorder Koggen (green), Drechterland (red), the Geestmerambacht (blue), and the Schager- en Niedorper Koggen (yellow). The board, consisting of a dike reeve and a few dike wardens, conducted an annual inspection of the dike. If the dike reeve found that maintenance had been neglected in any area, he could fine the farmer responsible.

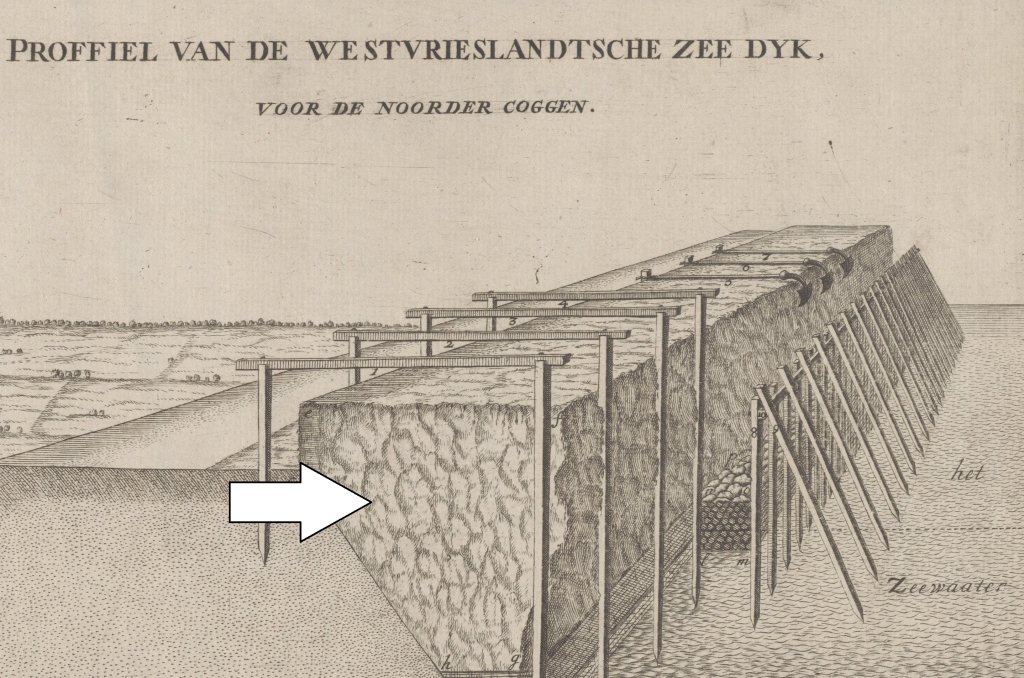

Around 1500, the area had become untenable due to ongoing soil subsidence. It was time for a large, strong dike. A meter-high cushion of seaweed was placed in front of the earthen dike body. This was intended to absorb the impact of the waves. Seaweed was harvested in the Zuiderzee between West Friesland and the island of Wieringen.

The seaweed package was clamped against the dike body with standing posts and a purlin of wooden beams. The construction was strong, but required a lot of maintenance. The seaweed eventually decomposed and the wood rotted. The water boards decided not to leave this specific maintenance to farmers. From then on, farmers paid water board taxes so that the water board could hire professional contractors.

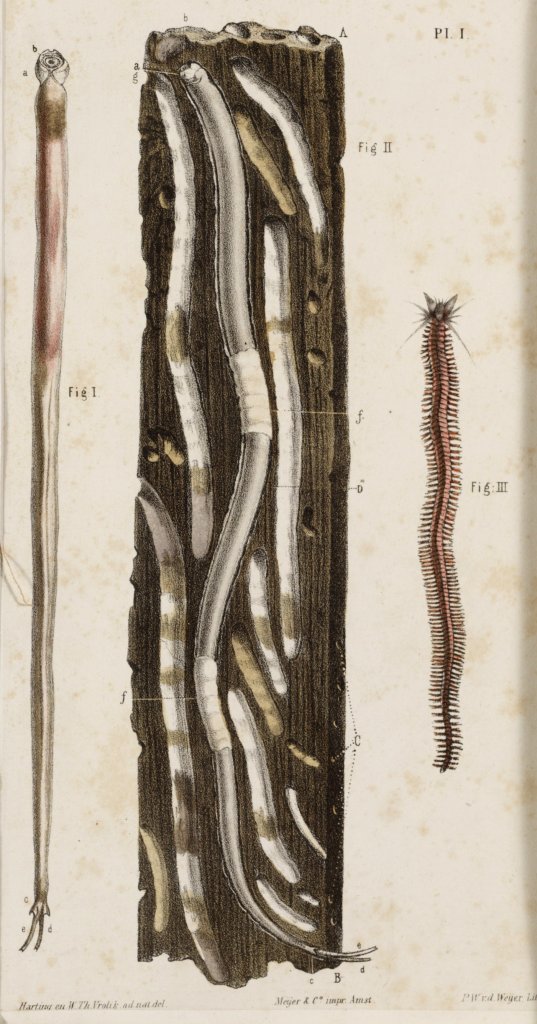

In 1731, the shipworm struck. This mollusk ate tunnels into the piles that held the seaweed against the dike. From the outside, the piles were still intact, but inside they were hollowed out. A storm would be enough to break them like matchsticks.

The water boards had to take action. They decided to replace the wood and weeds with a slope of Drenthe or Scandinavian boulders. It was a costly intervention, for which the water boards incurred considerable debt.

"It took longer to build than the pyramids, cathedrals, and the Great Wall of China," wrote Johan J. Schilstra (1915-1998) about the West Frisian Omringdijk in the introduction to his book 'In de ban van de dijk' (Under the spell of the dike). As a regional historian and member of the Provincial Council, Schilstra did his best to draw attention to the rich and valuable history of the dike. His efforts were successful, because in 1983 the dike was declared a provincial monument, the first in North Holland.