Hornsluis Lutje Schardam

Just above the village of Schardam lies the Hornsluis, also known as the Beemstersluis because for centuries the lock was managed by the Beemsterpolder. The name 'horn' is an old word meaning corner: just beyond the lock, two dikes, the Klamdijk and the Schardammer Keukendijk, meet at a sharp angle, or 'horn'. In earlier times, neighbourhood a hamlet in the neighbourhood called Lutje Schardam, or 'Little Schardam' in West Frisian.

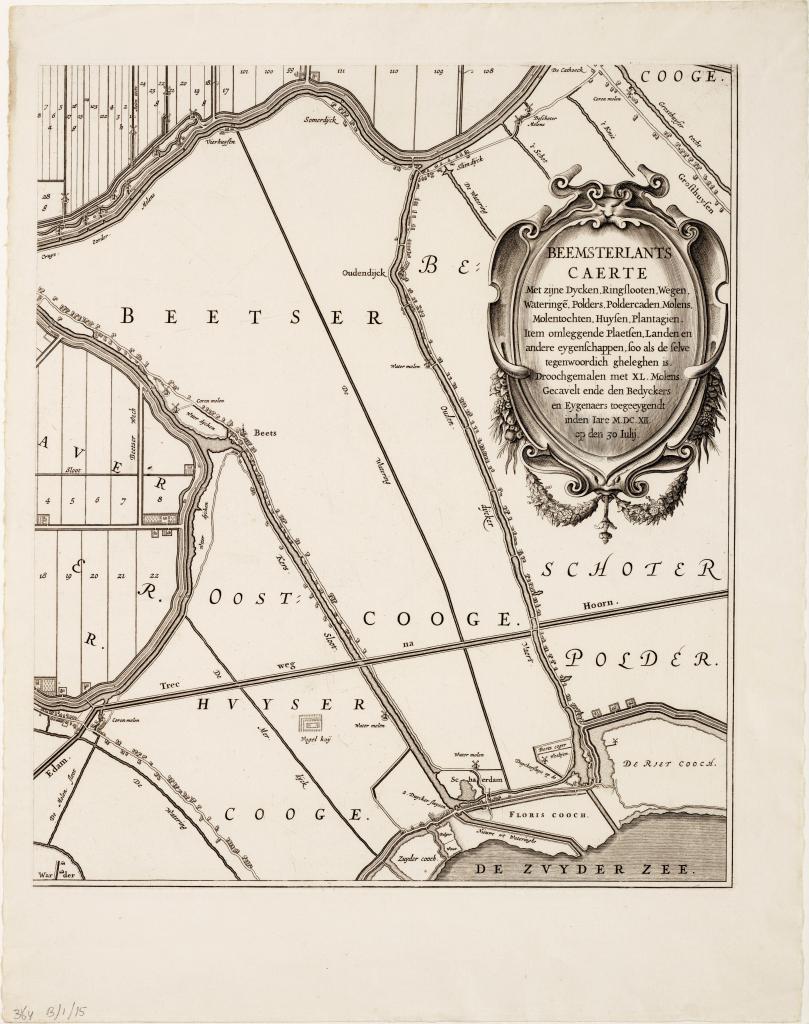

The lock was built as part of the waterworks that were necessary when the Beemstermeer was drained in 1608-1612. As a result, the so-called Schermerboezem lost 7,200 hectares of water storage capacity. The manager of the reservoir, the Hoogheemraadschap van de Uitwaterende Sluizen (Water Board of the Drainage Locks), therefore demanded that the Beemster construct a new drainage system from the Schermeer near Ursem to Avenhorn and further along Oudendijk to the Zuiderzee near Lutje Schardam. The drainage system was called Nieuwe Vaart in the 1630s, but has been given other names over the years.

Where the canal flowed into the Zuiderzee, a sluice gate was built in the sea dike to drain excess polder water at low tide. The Beemster remained responsible for the lock. A lock keeper lived next to it, and a small hamlet sprang up on the Klamdijk, making Lutje Schardam a little less 'lutje' (tiny). In 1638, it consisted of six buildings surrounded by a few trees, wedged between the dike and the Nieuwe Vaart. At the beginning of the 18th century, the hamlet disappeared again, possibly due to the dike improvements that were necessary after severe storm surges.

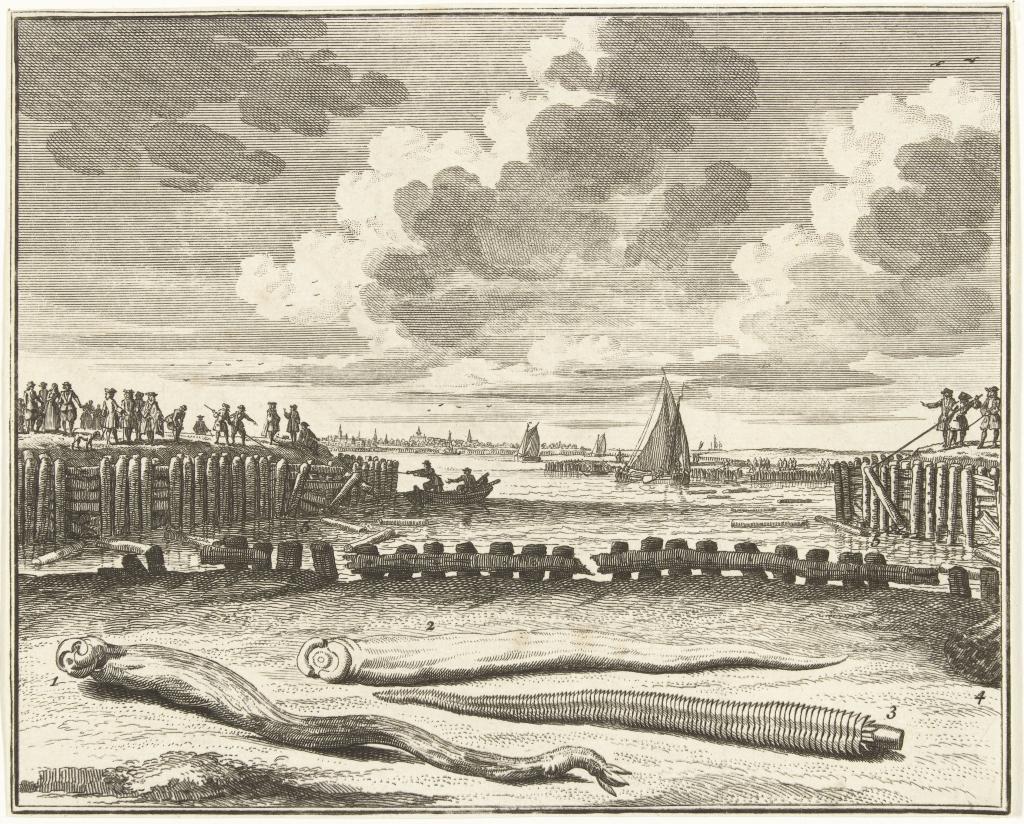

The lock was made of wood, like many locks at that time. Around 1730, however, the shipworm, a boring mussel that can occur anywhere, became a major threat. After a few dry summers, the Zuiderzee had become quite salty, allowing the salt-loving shipworm to reach the Hornsluis. In the summer of 1734, the dike reeve and the dike wardens had to conclude on site that the wooden lock had been severely damaged by the 'see gewormte'.

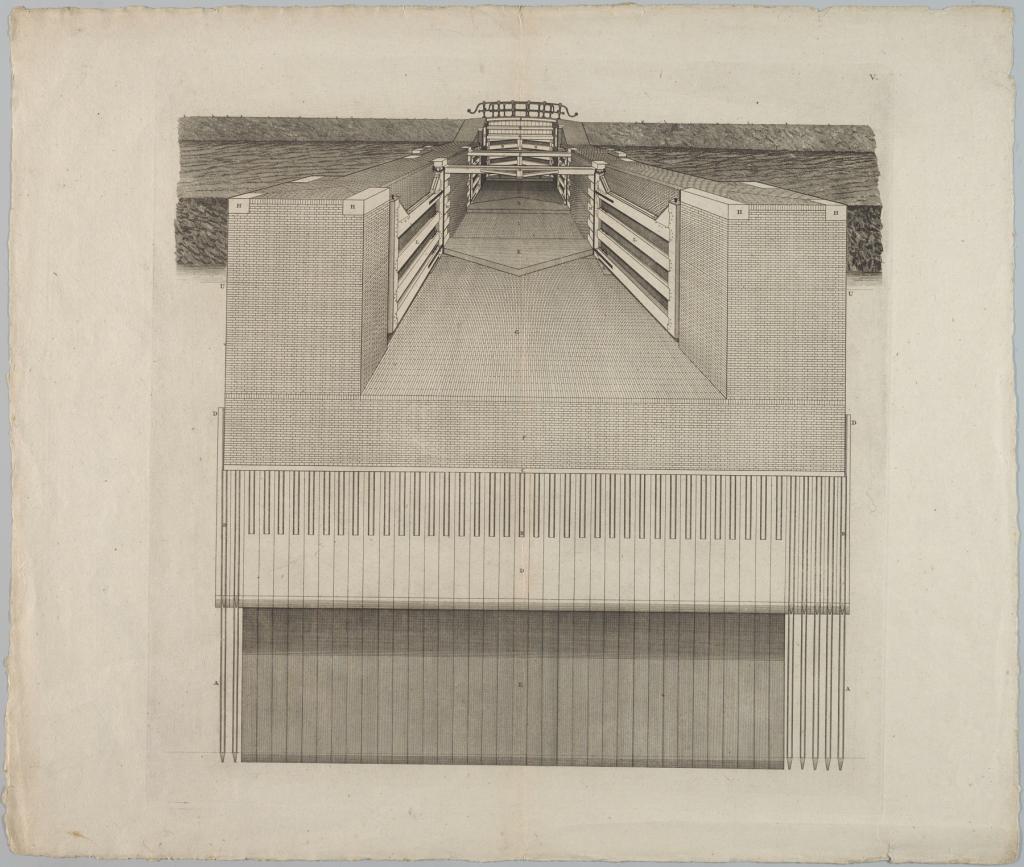

The polder board decided to build a brick lock and decorate it with beautiful sculptures. The stonemason and sculptor Thomas del Ferrier (1676-1755), an immigrant from Antwerp who had been living in Amsterdam since at least 1701, was commissioned to create two memorial stones. One stone shows the ‘Beemsterland coat of arms’, a cow in a meadow – a reference to the prosperity that dairy cattle brought to the Beemster farmers.

On the other side, a stone has been placed with a collection of nine colorful coats of arms, belonging to the dike reeve, the seven district reeves, and the polder secretary. Their names reveal that they were all city dwellers, hailing from Amsterdam, Edam, Hoorn, and Purmerend. At that time, the Beemster was still dotted with beautiful country houses belonging to wealthy city dwellers, such as Vredenburgh, owned by the fabulously rich dike reeve Dirk Alewijn (1682-1742) from Amsterdam. The city was then the boss of the Beemster countryside.

On July 6, 1735, the first stone was laid by two sons of prominent polder administrators. Jacob Alewijn (1725-1757) was the son of the dike reeve; Jan Pet (1728-?) was the son of council member Olphert Pet (1707-1766), who was also mayor of Purmerend. A silver trowel was ordered for both boys. Jacob's trowel has been preserved. The trowels were the work of Amsterdam silversmith Jan Willem Vastenouw (1700-1763), originally from Zwolle. In addition to an inscription, the coat of arms of the Beemster is also engraved on it.

The Hornsluis was designed by Evert Brant, master carpenter in Oostzaandam. The costs amounted to more than 34,000 guilders, but it was well worth it. The original iron railing of the bridge over the lock is still there, and when the dikes and locks had to be raised after the flood disaster of 1916, this was not necessary for the Hornsluis. After centuries of ownership by the Beemsterpolder, the lock was transferred to the Hoogheemraadschap van de Uitwaterende Sluizen (Water Board of the Drainage Locks) in 1941. In 1994, the lock was automated and the house next to it was sold to the daughter of the last lock keeper. However, the Hornsluis still fulfills its function today.

In 2021-2022, the Hornsluis lock will be modified with a new gate consisting of two parts. This will allow the lock to be closed partially or completely. As a result, the lock will be able to hold back high water when the situation requires it. At the same time, the function of letting water in or out will be retained.

Extra

- The Hornsluis is located on the walking route of the third stage of the Zuiderzeepad.

- Those cycling the Zuiderzee Route will also cross the Hornsluis on the Amsterdam-Hoorn section.