Jacob Claessesluis, Zijpersluis

Good water management requires cooperation. No water board can do everything on its own. But in the past, that cooperation sometimes left a lot to be desired. The Jacob Claessesluis is a monument that commemorates the centuries-long struggle between the Zijpepolder and the Hoogheemraadschap van de Uitwaterende Sluizen (Water Board of the Drainage Locks). The water board ultimately won—and wanted everyone to know it.

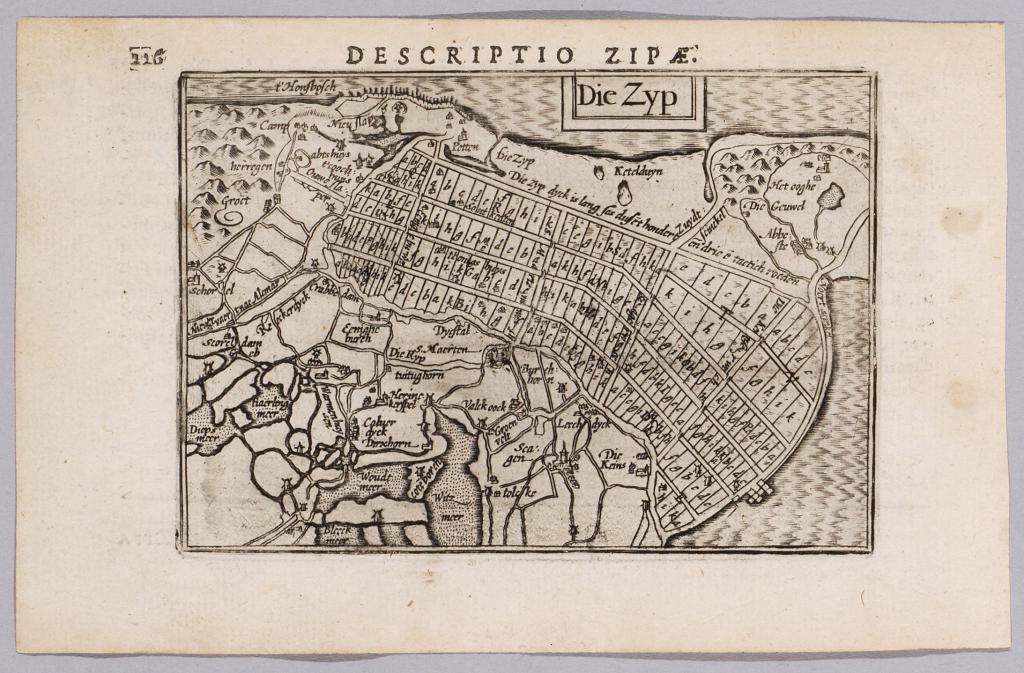

De Zijpe was the first major reclamation project in North Holland and, in many respects, also the most difficult. The new polder was repeatedly flooded. It was not until 1597, more than forty years after the first embankment was built, that De Zijpe remained dry. During the time that the Zijpe was 'at the mercy of the sea', some polder administrators did not give up hope. One of them was the Amsterdam merchant Jacob Claesz (1530-1587), who had been a member of the polder board since 1566 and treasurer of the Zijpe from 1569 until his death.

King Philip II played an important role in the difficult process of diking the Zijpe. In 1564, he gave the dike builders authorisation to construct authorisation lock in the Oude Schoorlse Zeedijk, so that the new polder could drain water and small ships could sail through. Why the lock was named after Jacob Claesz is unknown. People sometimes forgot this and referred to it as the 'Oude Sint Jacobs Sluis' (Old St. James' Lock) or the 'Zijpersluis' (Zijpe Lock).

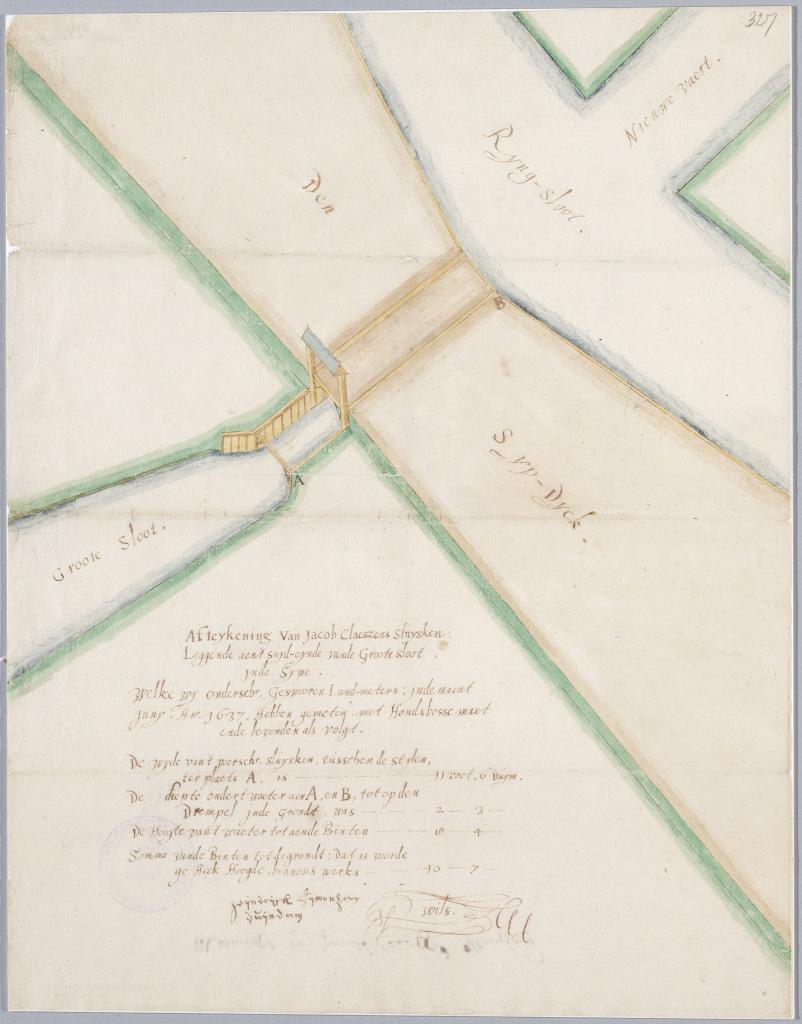

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the lock became notorious as the subject of conflict between cities and water boards with differing interests. In the 1630s, for example, the city of Alkmaar hoped to attract more trade by allowing seagoing ships to sail to Alkmaar from the Zuiderzee via the Grote Sloot through the Zijpe . However, Amsterdam and Haarlem put a stop to this and kept a close eye on ensuring that the Jacob Claessesluis was not widened.

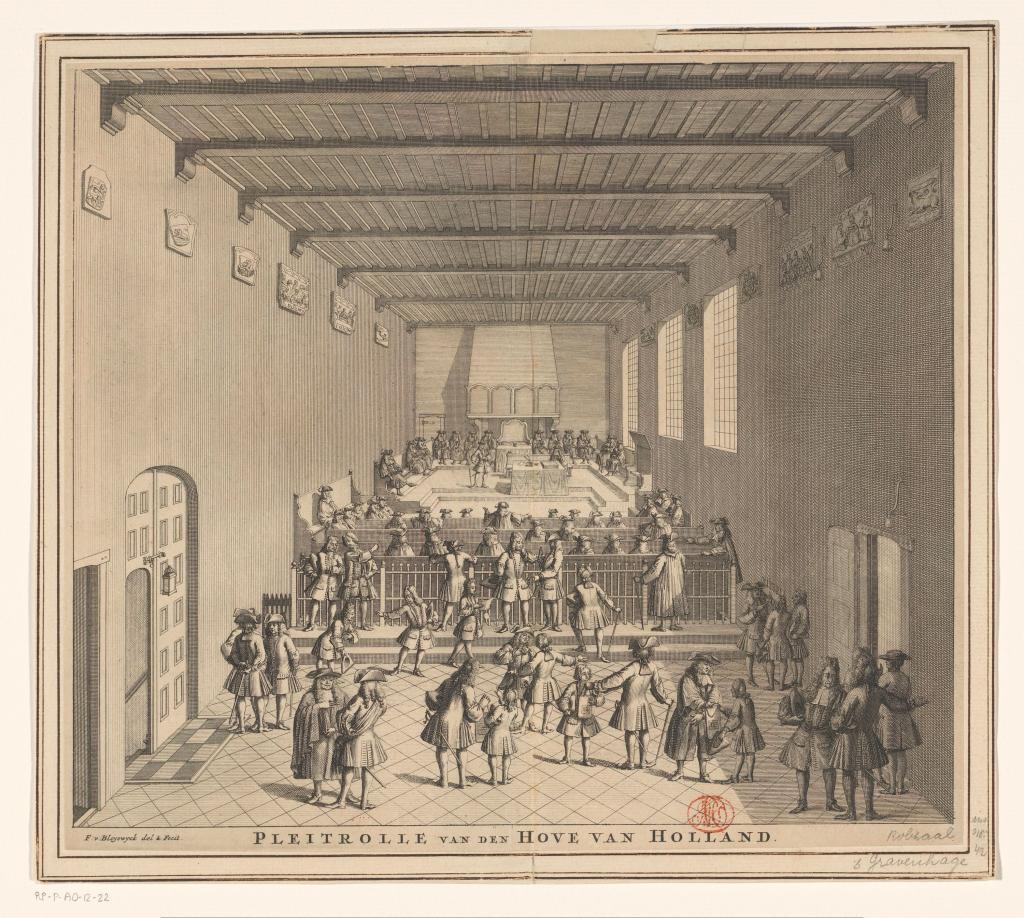

The Zijpe polder board and the Uitwaterende Sluizen Water Board also had a long-running dispute about the lock. The Schermerboezem, managed by the water board, needed to be able to drain northwards via the Zijpe during high water, but was often unable to do so because the polder kept the lock closed in its own well-understood interests. The water board therefore wanted control over the lock and fought long legal battles in The Hague – even though both the water board and the Zijpe polder were based in Alkmaar, close to each other.

Sometimes a solution was found, but centuries of dispute only came to an end in 1808. In 1797, the provincial government had assigned the lock to the water board, but Zijpe put up fierce resistance. The breakthrough came when the Netherlands became a kingdom in 1806. The landdrost, a kind of royal commissioner, could now decide that the lock belonged to the water board, period. From then on, Zijpe was only allowed to close the lock if the polder was threatened by high water.

The water board immediately had the wooden lock replaced by a much larger and wider stone lock that could be closed at high tide with lowerable sluice gates. Two lock chambers were needed because a single large gate would not work. The architect of the lock was the water board's 'master carpenter', Cornelis Kuyper (1757-1825), who was employed from 1782 to 1822. The Alkmaar stonemason Casper Josephus Bottemanne (1757-1812) was commissioned to make two large memorial stones.

On June 29, 1809, at noon, the first stone was ceremoniously laid by four children, the sons of the dike reeve, the secretary, and two water board members. Afterwards, the guests were treated to an elaborate lunch. Among them were the district administrator and seven dike reeves. The dike reeve of Zijpe and his water board members were present as guests of honor.

Whether the Zijpe polder board enjoyed lunch and dinner in Alkmaar that evening is not mentioned. In any case, the completed lock must have been hard to swallow for the board members: the Zijpe side of the lock now bore the coat of arms of Uitwaterende Sluizen. It was very clear who had won after all those centuries.

The family crests of the dike reeve and water board members of Uitwaterende Sluizen were placed on the north side of the lock. This gave Zijpe a beautiful 'gateway', as it were. In 1912, the sluice gates were replaced by flood barriers, which were stored in a small shed built next to the lock. The flood barriers were also only used when there was a risk of flooding. The lock underwent extensive restoration between 2016 and 2017.

Extra

- You can read more about the battle over the locks between Alkmaar and Amsterdam and Haarlem in the description of the Schermersluis in Nauerna.

- Zijpersluis is located somewhat in a remote area: anyone wishing to cycle or walk to the lock must take a shortcut via Krabbendam for part of the route over and around the Westfriese Omringdijk.

- The same applies to the third stage of the West Frisian Omringdijk Regional Trail.

- Another, smaller walking route in the neighbourhood is the Nuwendoornroute.