Stone sorting Westzaner Zeedijk

You need to know where it is, because otherwise you'll drive right past it, and you need to know what it is, because otherwise you might think, "Stones in a dike—so what?" But the 18th-century stone embankment at the bottom of the Westzaner Zeedijk near Nauerna is a monument that commemorates the devastating shipworm, which changed the appearance of Dutch dikes forever.

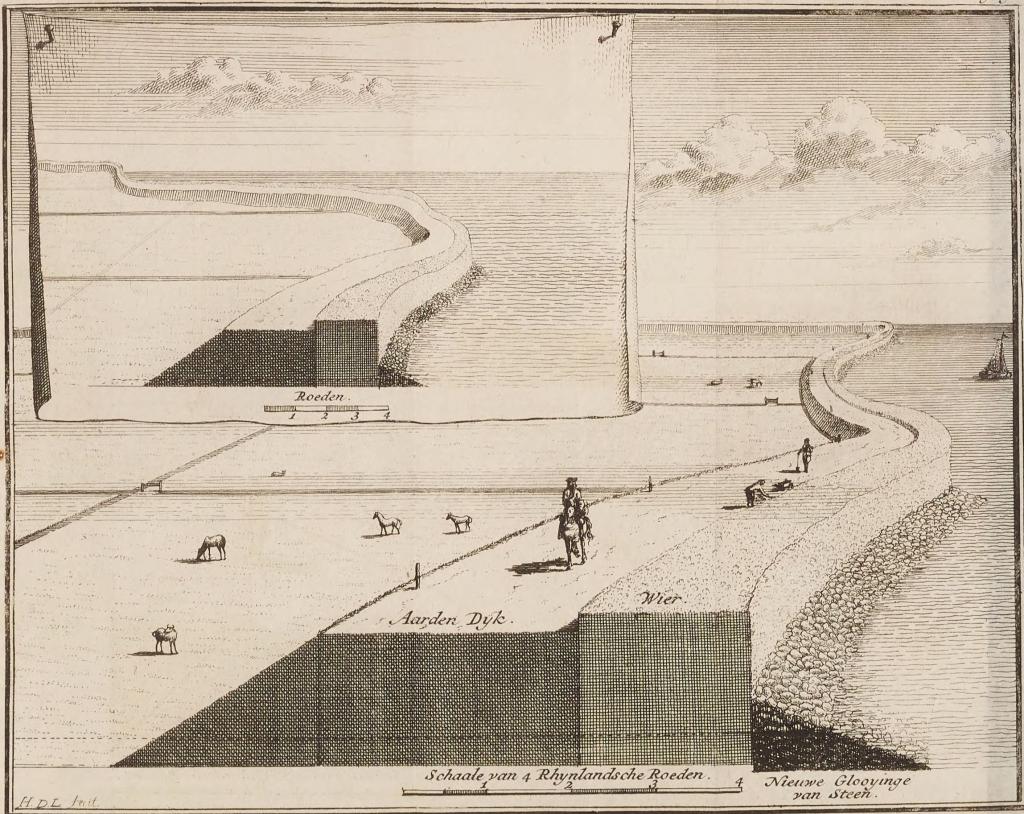

It was already well known in the 18th century that placing a stone slope at the bottom of a sea dike could effectively protect that dike against erosion during storms. The famous hydraulic engineer Andries Vierlingh (c. 1507-c. 1579) advocated the construction of stone slopes at all dikes as early as the 16th century. However, stone was expensive in North Holland, because the necessary natural stone had to be transported from far away.

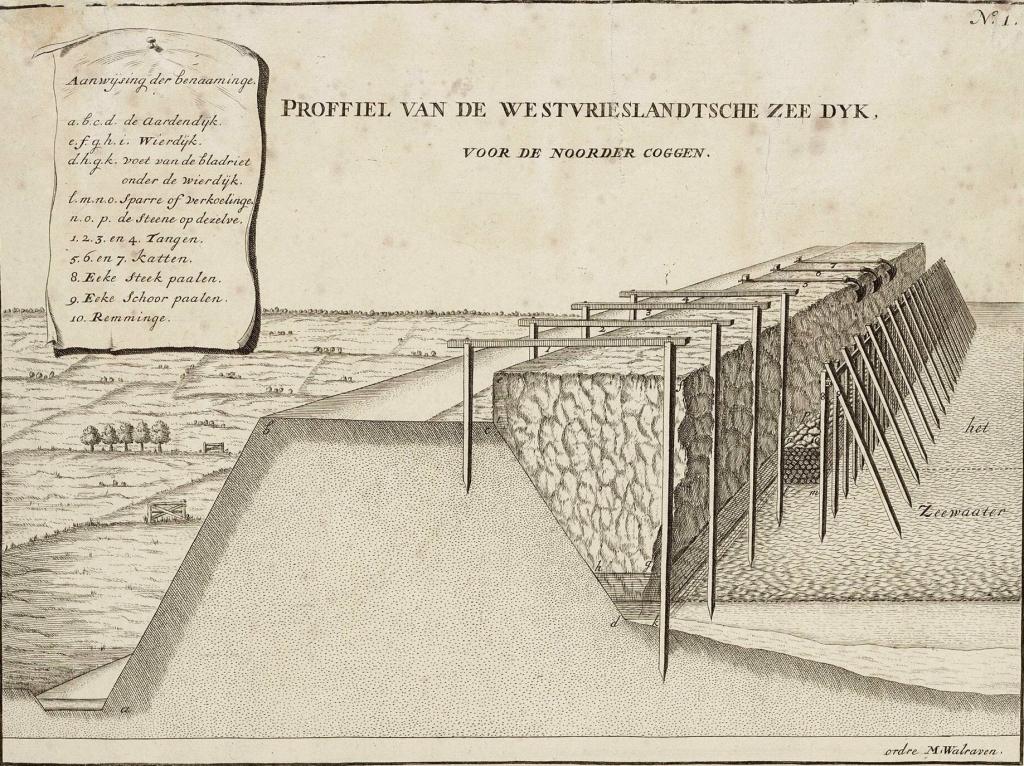

Instead, at the beginning of the 18th century, many North Holland sea dikes were protected against erosion by seaweed. In many cases, the foreshore outside the dikes had been completely washed away. For this reason, from the 16th century onwards, coastal defenses were often constructed on the seaward side of the dikes in the form of a seaweed belt or seaweed dike, composed of seaweed and wood. The seaweed was actually eelgrass, which grew well in the Zuiderzee, and wood was also abundant and inexpensive.

Dikes looked very different than they do today, almost like a wall in the sea. Compacted seaweed, held together by wooden stakes, formed a very sturdy substance that absorbed the force of the sea and thus protected the earthen dike from erosion. The seaweed held in place by wooden stakes had to be replaced from time to time and had to be replenished every year because it shrank, but it worked well for a very long time.

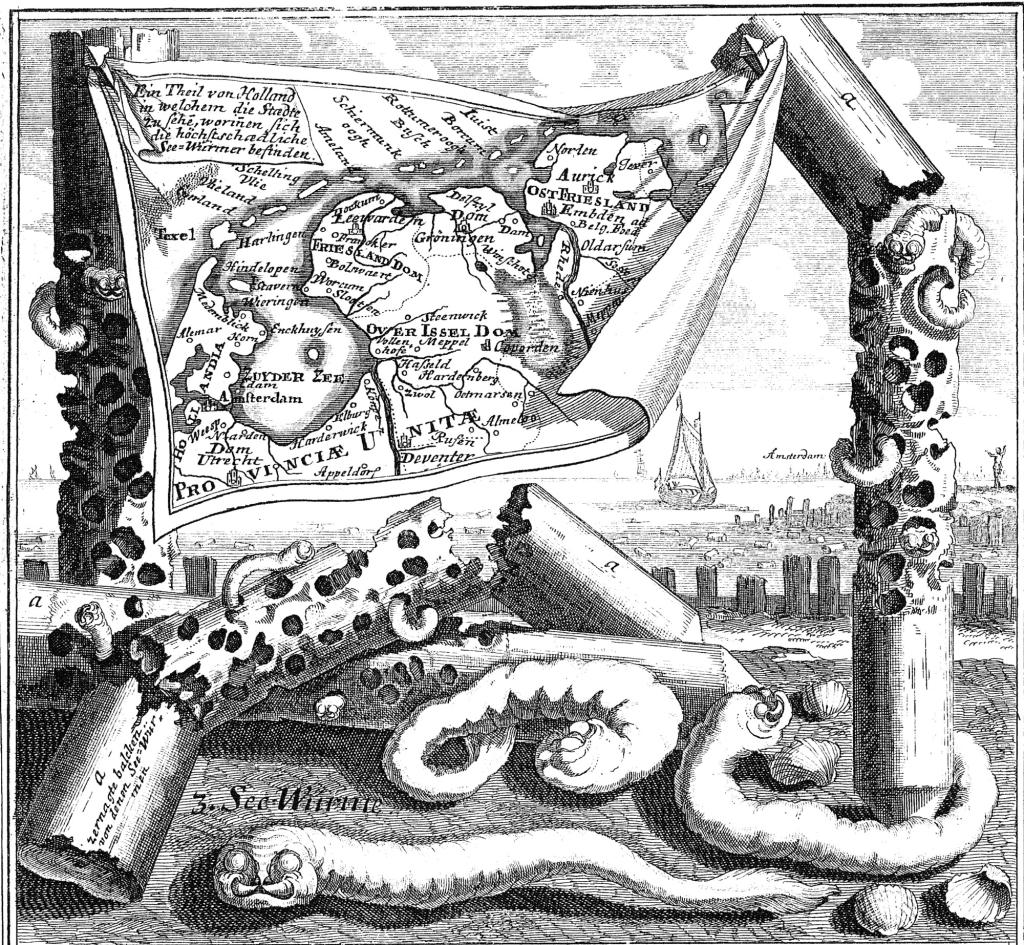

In the early 1830s, the piles that held the seaweed belt in place were found to be in very poor condition almost everywhere, much to the horror of water board administrators throughout the Dutch coastal region. They had been 'gnawed through' by a creature that was christened the shipworm. The shipworm (Teredo navalis) is a boring mussel that thrives in warm salt water and prefers to live in dead wood. Due to several years of warm weather and the salinization of the Zuiderzee due to a lack of fresh water, a veritable shipworm plague ensued.

The shipworm infestation came as a shock to the water boards around the Zuiderzee, especially those in North Holland. The beams and piles in the sea walls broke like matchsticks, and by 1731, the sea walls had already collapsed and drifted away in places. How could the dikes still be protected? Replacing the piles was pointless, as the shipworm would quickly weaken them again. All kinds of experts researched the shipworms and proposed various solutions, but nothing worked effectively. Many Dutch people believed that the shipworm was divine punishment for their misdeeds.

The best solution was ultimately proposed by two water board administrators from West Friesland, Pieter Straat (c. 1690-1751), mayor of Bovenkarspel, and Pieter van der Deure (c. 1685-1763), mayor of Grootebroek. In 1733, they advocated for a stone embankment to be built on the sea side of the West Frisian Omringdijk to keep the existing seaweed belts in place. This would be very expensive, but it would put an end to the shipworm threat and maintenance would be cheaper in the long run.

There was also a section of reed dike on the Westzaner Zeedijk, but most of the dike was protected with wooden revetments. The shipworm infestation meant that the dike had to be completely redesigned. The seaweed belt and revetments disappeared and, between 1735 and 1745, the dike was covered with a stone embankment. Tons of stone were brought in for this purpose and the people of Westzane received substantial government subsidies to pay for it all.

Much of the stone came from far away. The people of Westzaan ordered natural stone from Belgium, the Czech Republic, and Scandinavia. But rubble was also brought in from the old church in Westzaan, which was demolished in 1740. And perhaps chunks of dolmens were also included: due to demand from Holland, the people of Drenthe developed a thriving trade in stone. In 1734, a ban on the demolition of 'old famous monuments' was introduced, one of the first monument laws in history.

By 1745, the appearance of the Westzaner Zeedijk had completely changed. Wood had been removed everywhere and the dike had been covered with a stone skin. When the IJ was reclaimed, the sea dikes were left dry and the stone was reused elsewhere. For a long time, only the piece of slope east of Nauerna remained, which had been spared in 1948 at the insistence of Zaans Schoon. However, in December 2022, part of the stone slope on the Oostzaner Zeedijk was restored as a monument with 'Norwegian boulders' from the Markermeerdijk, at the request of the residents of Tuindorp Oostzaan. For them, the stones were once a favorite place to sunbathe or read a book.

Extra

The stone embankment is located on the Nauernaroute walking trail .

Anyone cycling along the North Sea Canal Route will also pass the stone embankment (near Groote Braak, where the dirt road bends).

This also applies to those cycling the Oer-IJ route.

If you want to see a wierdijk in real life, you should go to Wieringen, where the only remaining Wierdijk can be found at .