Drainage of the Raaksmaatsboezem

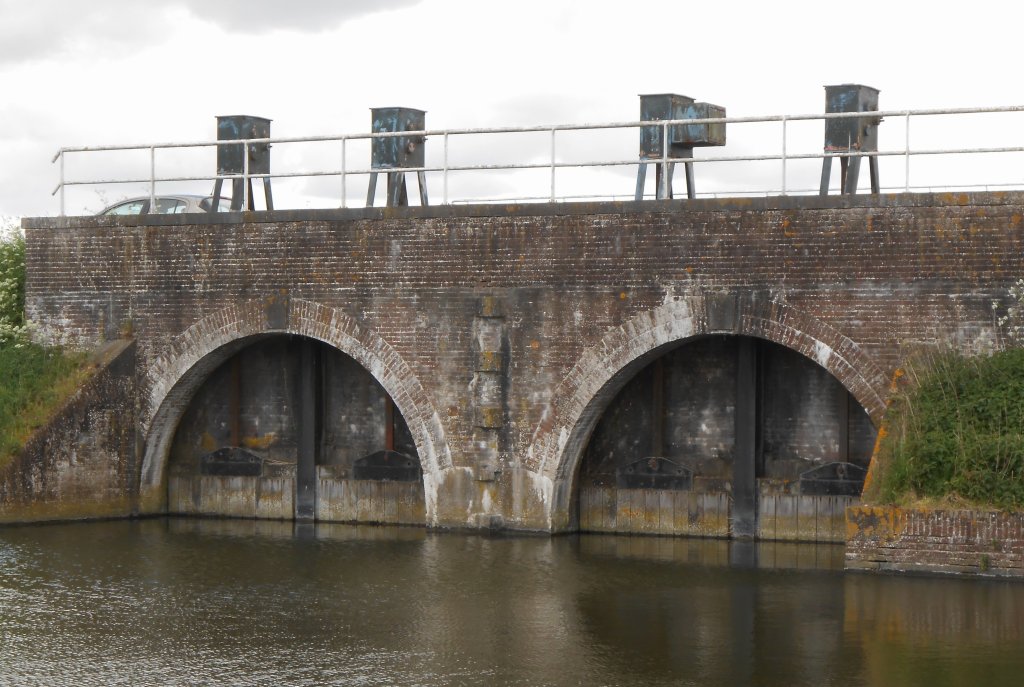

At the end of the De Rietput dike, we find a monumental lock dating from 1883. The road is private property. The residents keep access open as much as possible during the day, but on Sundays the gate is closed.

The lock was built by the former Geestmerambacht water board and served to drain the Raaksmaatsboezem water system. Raaksmaat means the measure of a raaks, a chain that was used in the past to measure land. The lock allowed excess water to flow into the sea.

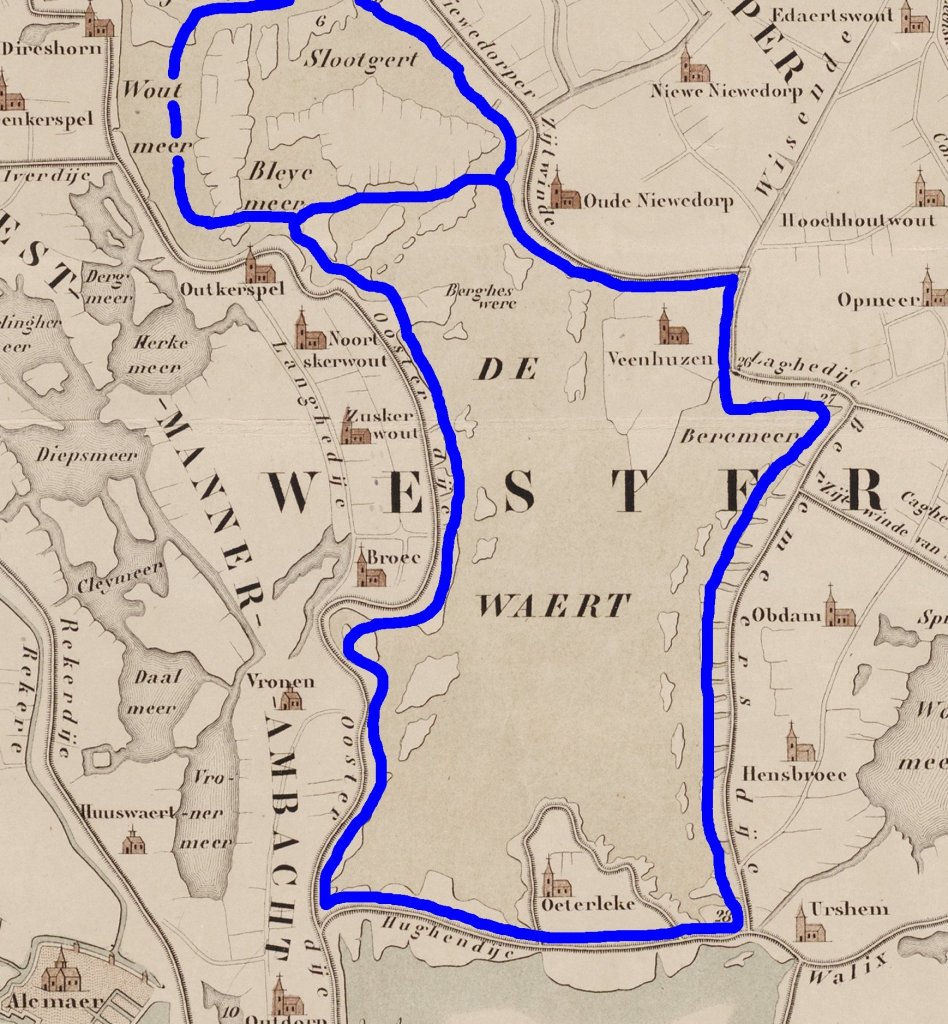

A (main) water system or reservoir is a network of large ditches, canals, or lakes into which polders drain water. The Raaksmaatsboezem originally consisted of a number of lakes, the most famous of which is the Heerhugowaard (Waert on the map). For centuries, these lakes were the drainage point for the surrounding polders. After 1600, however, they were all reclaimed as part of land reclamation efforts. This transformed the Raaksmaatsboezem into a system of ring ditches (dark blue). Naturally, this meant that much less water could be drained.

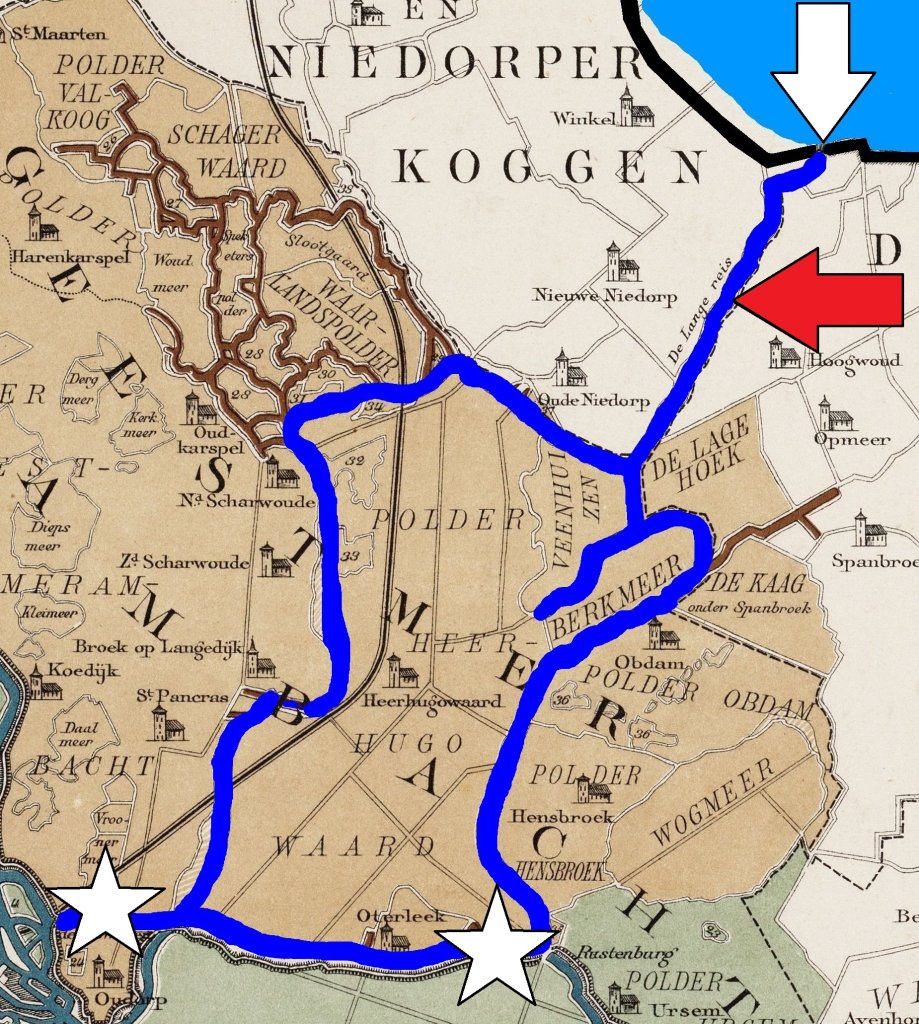

The pressure was high, because not only the old polders, but also the new ones depended on the ring ditches for drainage. In order to control the water level, there had to be drainage channels. Let's take the ring ditch of Heerhugowaard and Berkmeer as an example: at Oudorp and Rustenburg there are windmills that pumped water out of the ring ditch (stars on the map). In the north, the water could (and can) flow directly away through the Langereis canal (red arrow). This runs to the Omringdijk. At low tide, water was discharged via two sluices in the dike (white arrow).

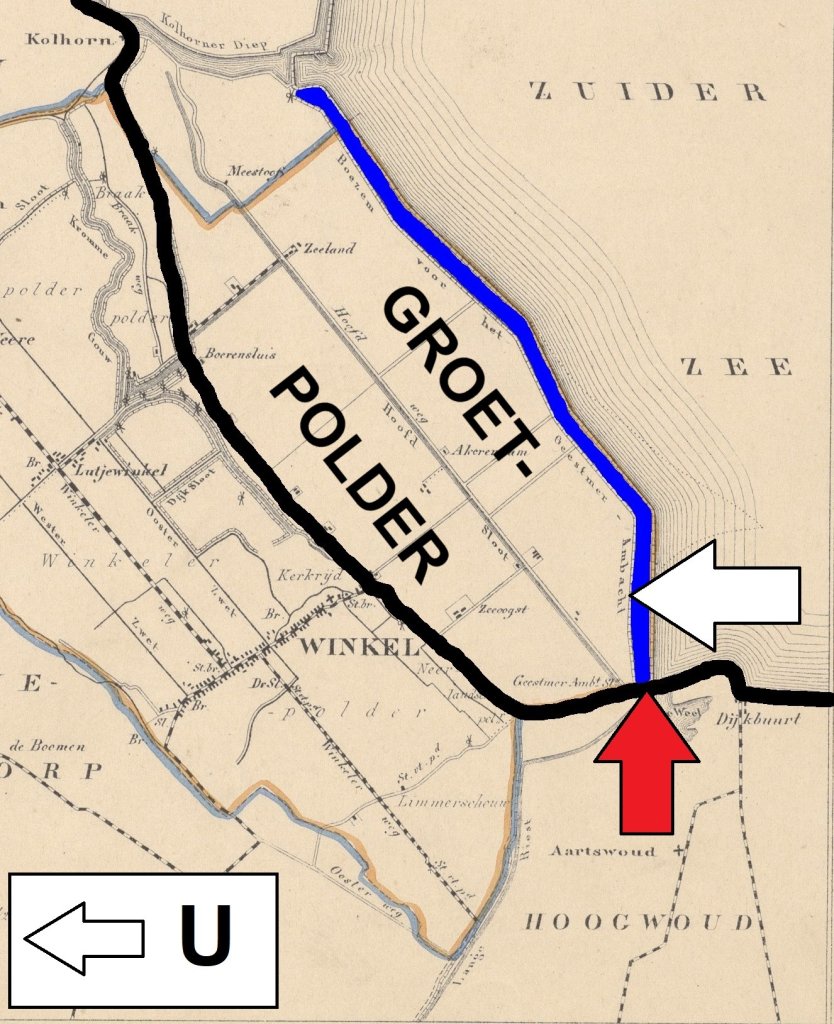

The Groetpolder was established between 1844 and 1847. As a result, the Omringdijk (black line on the map) and the sluices (red arrow) were no longer located by the sea. The Geestmerambacht Water Board therefore negotiated a drainage canal. This ran from the sluices along the entire length of the new polder to Kolhorn (blue). There, the water could still be discharged into the sea. For the dike builders of the Groet, such a long canal was a financial setback. It took up valuable space and required maintenance.

Why did the Geestmerambacht want such a long canal? To have sufficient water storage for periods when it was difficult to discharge water into the sea. In 1883, the water board revised its opinion: the water from the Raaksmaatsboezem could be discharged closer to home. And so, four hundred metre of the Omringdijk in the dike of the Groetpolder, this brick lock was built. The canal was filled in. Only between the Omringdijk and the new lock did a drainage channel remain, of course.

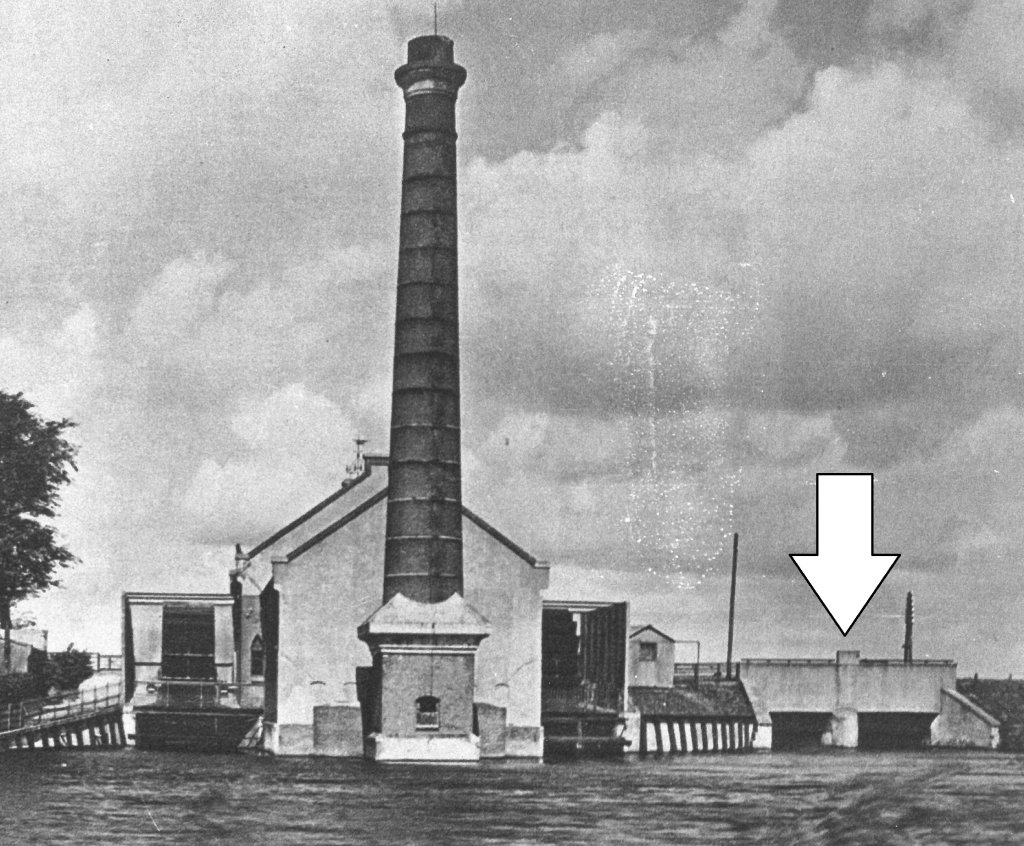

In 1894, the Geestmerambacht had a steam pumping station built near the old locks in the Omringdijk (arrow in the photo). It operated until 1960 and was demolished in 1970. Steam power made it possible to speed up the drainage of the Raaksmaatsboezem. This was an important improvement, because the water level in the ring ditches and canals was often so high that the polders could not drain the water. This resulted in flooding.

The19th-century lock (arrow in the photo) is still in use, but the water no longer flows directly to the sea. When the Wieringermeer was drained in 1930, a new solution had to be found for draining the Raaksmaatsboezem: the Waard and Groet Canal, which flows into the Amstelmeer.